An article about Berlin caught my attention last week and, like Proust’s madeleine, it transported me back to a different time and place.

My friend, Bernd Hummel, is a successful German businessman with a fondness for America and Americans. As a child in Germany at the end of World War II he remembers American soldiers handing out candy and gum to the kids in his small town, and he hasn’t forgotten their generosity nor lost his gratitude for how America helped rebuild Germany. He shared that part of his story with me in 2014 and showed me two sections of the Berlin Wall he purchased and installed in the courtyard of his office complex two hours south of Frankfurt. He knew that I had lived in the shadow of The Wall for almost 10 years and that I would be curious to know their back story.

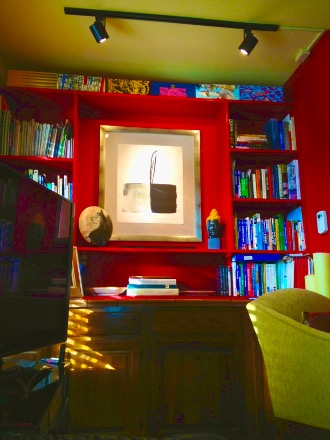

As he explained it, these sections of The Wall have their own tale. The Wall was actually two walls separated by a No Man’s Land of barbed wire and landmines. These two panels, from the eastern wall, were painted by an East German high school art teacher in the days after the Iron Curtain fell as the two Germanys were struggling toward reunification. Until then, the graffiti covered wall on the west side was a widely discussed art enterprise and tourist attraction, but the eastern barrier was unadorned concrete. For years the East Berlin art teacher had wanted to decorate his side of The Wall but was forbidden from following up until November 9, 1989 when the DDR (Deutsche Demokratische Republik) collapsed and its citizens allowed to cross the “grenze” to West Berlin safely.

No longer handcuffed by the DDR’s security apparatchiks, the art teacher began furiously decorating 20 sections of the east wall, but within a year, as reunification approached, the government began tearing the whole thing down. In the chaos, an enterprising former East German army officer, out of a job, saw an opportunity to profit and quickly dismantled the artist’s painted sections and hid them temporarily in a marshy wetland nearby. A year later when it was clear that there was collector interest, he offered them for sale through a Berlin auction house. Bernd got wind of the sale and purchased two of them. The artist is lost to history and was not included as a beneficiary of the sale – one last victory for the East German army over an East German artist.

This picture of The Wall from the west shows its famous graffiti art (and the “death zone” between the east and west walls, where barbed wire, landmines, guard towers and roving police dogs prevented East Germans from crossing over to West Berlin.

My own first visit to Berlin was a one week stay in January of 1966. Perhaps no city in the world, certainly none in Europe, has undergone anywhere near the magnitude and number of transformations in the last 75 years, and I feel fortunate to have witnessed and experienced several of them.

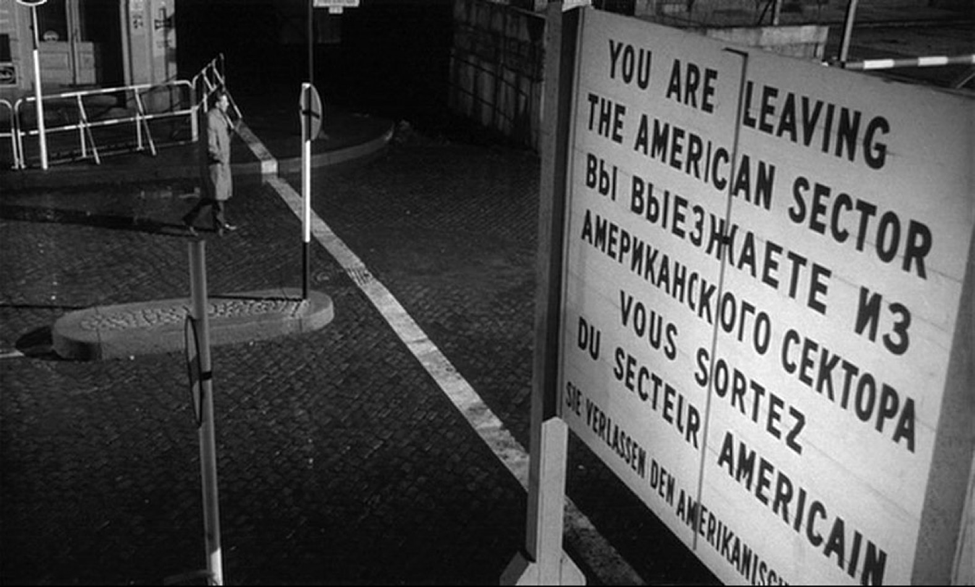

On that 1966 stay, the Wall was only four years old and the Cold War was at its frostiest. I had arrived alone by train at the Bahnhof Zoo and found a small, inexpensive pension nearby. The city was cold, gray, and lonely in mid-winter, but over the next week I explored it on foot from Dahlem to the bomb damaged shell of Kaiser Wilhelm Kirche – but, my most memorable experience was a solo excursion to East Berlin. I remember it all in black and white. Except for the blazing, neon, Mercedes logo atop the new Europa Center the city was colorless that winter.

It should be remembered that at the end of WWII Berlin was divided into four sectors – British, French, American, and Soviet – with free passage between sectors. It wasn’t until The Wall was erected in 1961 that traffic between them was restricted. Until then, the two underground rail systems – U-Bahn and S-Bahn – provided easy access to all parts of the city. Service between West Berlin i.e. the British, French, and American sectors, and the Soviet sector was disrupted by construction of The Wall and free passage was interdicted. Only one stop remained open for passengers wishing to cross the border in either direction. The station at Friedrichstrasse on the S-Bahn line was the intersecting junction and the underground version of Checkpoint Charlie.

My own transit to East Berlin began with a morning ride on the S-Bahn and arrival at the dimly lit Friedrichstrasse S-Bahn stop. Just inside the hall adjoining the underground platform was the customs checkpoint with its yellowing tile walls, officious uniformed agents, and sour-faced, young Volkspolizei (VoPo’s for short) with their shoulder slung AK-47’s. While my papers were being checked and re-checked I observed the scene and wondered if it was really a good idea to be wandering around East Berlin alone. Eventually, I cleared Passcontrolle, purchased the required number of East German Marks, had my temporary visa stamped, and climbed the stairs to enter the dystopian paradise of the DDR.

It was mid-winter cold with a soot-gray overcast and dirty snow banked in the shadows of the monotonous, ugly, Eastern-block, apartment houses that lined the empty streets. Well, almost empty… As I started to walk in the direction of the Pergamon Museum, the only site I could think of to visit, I picked up a fellow-traveler, a young guy who followed for a couple of blocks and then sped up to walk beside me.

Like most solo American visitors, I assumed he was a “tail,” assigned to follow and figure out the purpose of my visit. He was obviously young and inexperienced, and his spy-craft was rudimentary. When he did approach me he was overly friendly and awkwardly asked a series of mundane questions (in English). “What is your name. Where are you from? Where are you going? Do you want to buy East German Marks? Would you like me to guide you?”

Apparently my answers satisfied the “guide” that I was not a spy. He said “goodbye,” and I proceeded on to the Pergamon Museum. Today the Pergamon stands on “Museum Island,” an important stop in any exploration of the city, but in 1966 it was more a dimly lit, bullet-riddled ruin than a museum. Later that afternoon I returned to my West Berlin pension and concluded the East Berlin excursion without incident. I was relieved to be back on “my” side of The Wall. Today, when I read Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, I picture Smiley standing near Checkpoint Charlie with a dirty gray sky and bullet marked buildings as he awaits Karla or some other double dealing Russian agent.

In another Berlin thriller, the most riveting scene and the one most applicable to this story of The Wall is the conclusion of The Spy Who Came in From The Cold. LeCarre’s dark, byzantine, spy novel ends with Leamas, his protagonist, and Liz, his girlfriend, attempting an escape to the West. As Leamas reaches the top of The Wall he extends a hand to Liz just as the spotlight from a nearby guard tower catches them in its beam. Liz is shot, and the story ends with Leamas’ capture and certain execution.

Today, when I look at Bernd’s two sections of the Wall I am reminded not only of these dark spy novels but more importantly of the many true stories of attempted escapes with real bullets. I’m also reminded of how many Berlin stories I have to tell, including my East German friend’s scuba escape under the Danube River from Budapest, Hungary to “somewhere” in Austria. But I’ll save that one for another time.