Do you ever wonder about your ancestry? Do you know how and when your family came to America? Is there any strange fruit hanging on your family tree? Einstein? Al Capone? Sarah Bernhardt? What do you really know about your family’s history?

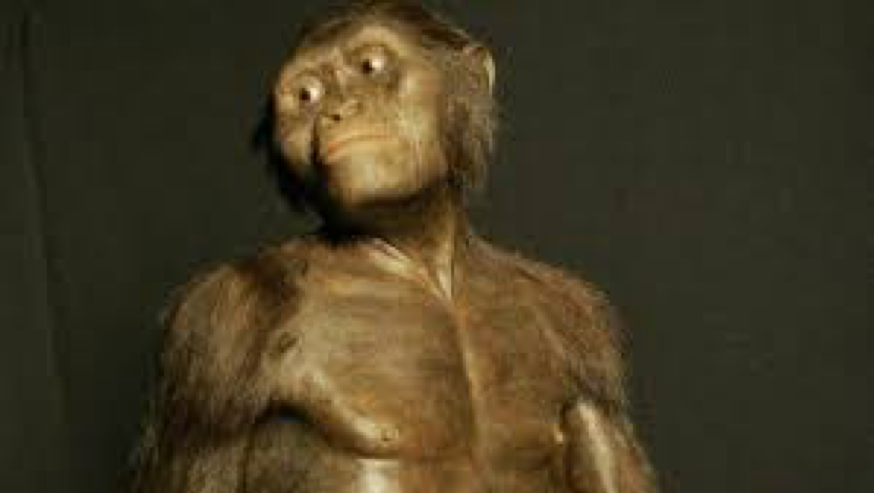

Are you a true American? Probably not; Elizabeth Warren’s recent DNA test confirms that she is, because her ancestry links back to those who inhabited North America before 1600. They’re the only true Americans. The rest of us are immigrants or descendants of immigrants. Even Donald Trump’s tangled roots are buried in one of those “shithole” countries in Africa he likes to disdain.

Like most Americans, I didn’t know a lot about mine–when did the first Bernards arrive in America, where did they come from, or how to find the answers to these questions until recently. I hadn’t really thought much about it until I was living in Berlin and a friend questioned me about it. When I told her I didn’t know much, she was stunned and walked me over to a framed picture hanging in her entrance hall. It was a drawing of her own family tree dating all the way back to 1500. I learned later it was common for Germans to build those family trees – true or false – because the Nazi’s were always checking for genetic purity. Nevertheless, her question piqued my curiosity.

My own parents, like many American parents, seemed reticent to talk about family ancestry. I didn’t understand it, but it didn’t seem that unusual. My mother was an only child of older parents and I sensed her childhood was an unhappy one. My father was the youngest of five siblings, 17 years younger than his next oldest and raised mostly by his older sisters. Neither my mother nor my father offered me information about our lineage and I didn’t press them for it. To be fair, they might not have known much. In the early days of the republic and the rush westward to a better life, a lot of family histories were lost or forgotten.

I accepted the conventional wisdom that immigrant families were anxious to assimilate and distance themselves from their foreign roots and chose not to pass on the story of their origins. I had no reason to believe that about my family, but there was an absence of information so it made sense.

Because my parents didn’t talk about it, family history didn’t seem important. At one point, to fill in the blanks, I concocted a story about a French heritage, plausible in my own mind because Bernard is a French surname and I’ve always been a Francophile. But it was bogus, and I started to unpack the family history when my mother died and a distant cousin sent me information she had uncovered about our family’s roots.

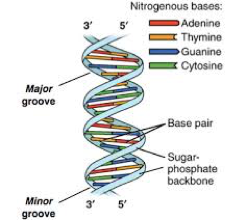

Since 1953, when James Watson and Francis Crick broke the code – literally broke the code –and discovered the structure of the DNA molecule (double helix, below) it’s become increasingly easier to trace ancestry. Genome scientists have expanded the decoding and today ordinary mortals can send a saliva sample to various commercial enterprises such as 23 and Me or Ancestry.com and unlock the door to their genetic provenance.

Recently, with information from 23 and Me, I discovered that Bernard ancestors, mostly Irish and Scottish in origin, settled in Virginia before America became nation. We weren’t fugitives after all, and from a farm near Thomas Jefferson’s estate at Monticello in the 1700’s the family slowly moved west over the next 200 years.

My favorite Bernard story, maybe a metaphor for the whole clan, involved two distant cousins. Uncle Sam and Uncle George who had reached Colorado just before the Gold Rush at Cripple Creek. In 1892 they opened a grocery store to supply the miners, and according to “The Ghost Towns of Colorado,”

Sam took over William Shemwell’s half interest in the Elkton claim for canceling Shemwell’s $36.50 grocery bill, and Uncle George paid Sam Gee, a “colored ash-hauler,” $50 for his one-eighth interest. George then financed the development work for two years until he was just about broke and the Elkton was about to be abandoned. Then they hit pay dirt–$40,000 in the first week. Eventually, the Elkton produced gold worth $16,000,000. Later Sam Bernard got control of another rich mine, the Beacon Hill El Paso—an $11,000,000 producer.

The Bernard boys took their millions and more or less retired from mining in 1902. George bought a huge ranch north of the Springs and raised blooded cattle. Sam went in for trotting horses. But, George died practically penniless in 1933. Sam died in ’37 an indigent patient at Colorado State Hospital (the state mental hospital).

As Kurt Vonnegut would say, “So it goes.” The Bernards and their money are soon parted, but it’s a good story and we like good stories. Thanks to DNA science and the expansion of genomic and genealogical resources, we can all learn more about our families.

In the past, I’ve asked myself “Why is family history important?” I still don’t know the answer, but as the last remaining member of my generation it “feels” important. Of 5 uncles and aunts and 10 first cousins I am the sole survivor. Ancient cultures have always had a tradition of passing their ancestry information to succeeding generations. At this point, I wish my parents had talked more about it.

The more I learn about my ancestors, the clearer the picture of the American timeline becomes. Pre-revolutionary immigration, the acquisition of land, the establishment of homesteads, child mortality, hard farm labor, the halting trek West, education as a way to a better life (my uncles and aunts were all college graduates before 1920), and improvements in the quality of life. My father was born the year the Wright brothers flew at Kitty Hawk, and 55 years later I flew an airplane at 1000mph.

America is a land of immigrants and opportunity. Mr. Trump wants to close the door, pull up the ladder and dump the people of color overboard. My family would probably pass the Trump test, but I have grandchildren, close friends, and neighbors who would not. We can’t let him close the door. Immigrants and diversity have made America as great as it is. Embrace it. I’m glad to have learned more about my ancestry. I plan to learn more. The information is out there, but sometimes it takes a little digging to untangle those roots.